Dear Friends,

Wednesday mornings, you can usually find me huddled with Whitney at Table 20 (the 2-top closest to the parking lot door) going over our promotional efforts, including what I might write for the week's email. This week, Whitney had a pretty good suggestion - chronicling the journey of a single croissant all the way through the production process. In truth, I have been pleased with their quality lately, so the idea stuck.

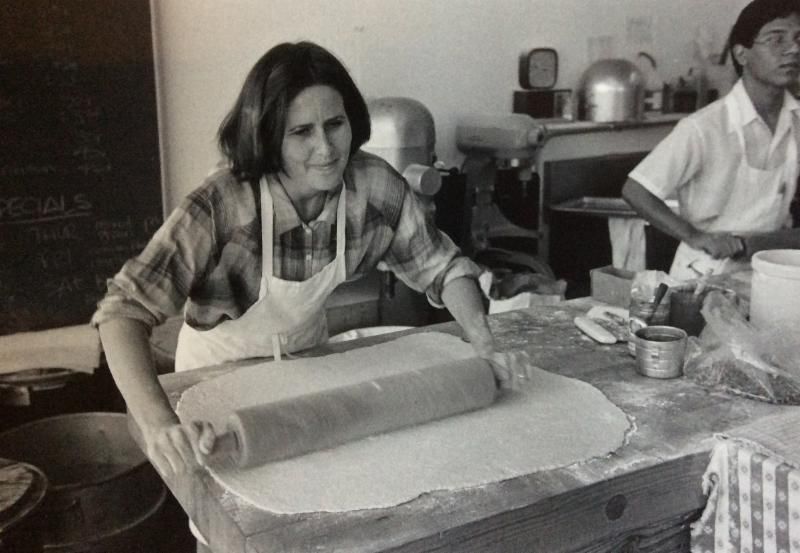

This set me thinking about the old days, when I first learned to make croissants from scratch back in late 1981 or early 1982. I have vague memories of sidling up to the butcher block counter and slicing up whole sticks of butter; of mom showing me how to lay the sliced butter flat on a piece of hand mixed dough, then how to fold it in on top of itself, roll it back out and repeat the motion three to four times.

We used these very small French rolling pins (solid pieces of wood that tapered a bit at the ends) and worked with very small batches of dough that only made about a dozen croissants each. Once the dough was buttered, it had to rest overnight in the fridge before it was soft and pliable. The next morning we would roll it out thin and cut the triangular pieces that would be shaped into croissants.

All that folding gave the crescent shaped pastries a lot of resilience, and it was fun to watch them rise to triple their original size. I learned that you had to watch for the perfect moment to paint on the egg wash that would make them shiny when you sent them to the hot oven. Too early, and they would come out tight and restricted; too late and they would flatten, failing to "pop" in that explosive, yeasty growth spurt that you wanted to see when they baked.

In those days the bakery sat at the northeast corner of 34th & Guadalupe in what for years had been a TV repair shop. It had these beautiful old casement windows that they don't make anymore - the kind you could reel out with that little hand crank at the bottom. Each of these tall rectangular windows had 3 or 4 panes of glass and a metal screen that mounted on the inside.

Stopping at TFB you might pull into one of the diagonal parking spots that abutted our front door at a 45 degree angle. On a weekend, you would queue up for a warm pastry, maybe with a copy of the New York Times under one arm - the line would extend all the way past the bakery to Ropa Usada, the used clothing shop next door (later to become Amy's first ice cream shop). And once you had your pastry and a styrofoam cup of Anderson's house blend, you might browse the bins at Recycled Records (adjacent to Ropa) - a fine place to buy used records. (I still own the 1979 cherrywood D-25 Guild guitar I bought from a guy named Chuck who worked there).

Across Guadalupe was an old red and white fifties-style modernist Conoco Station, where a gas station attendant would come out to pump your gas and check your oil while you sat comfortably in your car and kept your hands clean. UT All American defensive lineman Kenneth Sims worked there part time before the Patriots drafted him No 1 overall in 1982. I guess D-1 athletes could have jobs back then.

Next to the Conoco was the big pink house (still there) that housed Janet Maples' hair salon, the Scarlet Angel. Zelda cut my hair. She lived in a brick duplex behind us on 32nd street with her girlfriend Annette. I used to sneak across the alley behind our house and smoke grass with them, and I remember hearing Emmylou Harris's Elite Hotel at their house for the first time. After they broke up and Zelda moved to San Antonio, I called Annette, who still cuts my hair these days.

Alan Goldstein came to work for us around that time. Alan lost a leg in a tragic roadside accident near Beaumont when he was in high school and he wore a prosthetic from the hip down. When kids would come into the bakery, Alan would sometimes sacrifice a pair of perfectly good blue jeans, stabbing a butcher knife through them, deep into his prosthetic leg. This awesome move was good fun for the whole family.

But I suppose what I really remember is the way it felt to casually assume that all of these people and things would just be there. I guess there comes a moment for each of us when we realize this is not true. Impermanence is fundamental to our human experience. Small changes roll in one on top of another and pretty soon they're not so small anymore.

I guess I'm thinking this way because last week we lost Howard Rose, a dear, dear man and simply a one-of-a-kind friend of TFB (and of mine). Here's a link to a short obit, which mentions Howard starting the law firm that became Brown McCarroll, working as Governor Connolly's chief of staff, etc.

When we were first introduced, I called him "Mr. Rose" in deference to his age and accomplishment. He just looked at me with this big smile and said in his gruff but friendly voice, "Murph, if you don't call me Howard, we're not going to get very far."

One day I got really irritated with him. I saw a homeless man approaching him to ask him for money as he was getting out of that late model four door Cadillac he drove. I raced toward the scene of this crime hoping to break up the transaction. But before I could get there, Howard had his wallet out and was handing the guy $20 - yes, $20. I was trying to process this, shaking my head, as I ran the guy off. And I suppose it was only much later that I realized Howard had just schooled me in how to be a decent, generous human being.

They don't make them like you anymore Mr. Rose. I'm going to miss seeing you in our dining room something fierce. You treated me with more respect and love than I felt I deserved and you made me want to live up to what you seemed to see in me. I'm going to do my best sir. Peace be with you.

For the rest of us, I'll leave it at this: if you want to be part of our community, please come join us. At times like these, when the world seems completely crazy, what we have is each other. We have a place for you.

bon appetit,

murph